This text is about the context of the works which will come together in the second issue of the magazine, the first issue of which has been published under the title “06.2020/14/dergi”. The founder and coordinator of the mentioned periodical is the artist Sergen Şehitoğlu. Şehitoğlu has created a periodical which has included in its first issue 14 works produced by 14 artists for a medium in the form of a magazine. This periodical creates a quite different context than the traditional context of exhibiting in which art objects usually emerge. In a manner of speaking, we can consider this periodical as a medium which realizes intangible exhibitions.

In Turkey, there are various periodicals initiated, developed and still being published by people, who realize intellectual activities in the fields of philosophy and science, for their own intellectual needs. But as far as I know, there are no such periodical media created for the intellectual needs of people, who realize intellectual activities in the field of art.

Certainly, there are various periodicals informing us about activities in the field of art, however, these are not media which, like the magazine initiated by Şehitoğlu’s personal devotion, include individual works of art produced by artists with the anticipation of being presented in a periodical where these works come together to create a context of a kind of exhibition; but rather, they are media consisting of textual contents, accompanied by numerous advertisements, legitimizing specific objects in the context of art as they emerge in venues such as galleries, museums or institutional spaces within traditional forms of exhibiting. In the manner of speaking, since publications of the first kind are realized by the artists’ personal devotion and participation, they eliminate the division of labour in the field of art and materialize the intangible value of art; while publications of the second kind are media which, by including contents about big production exhibitions requiring much more division of labour, materialize the tangible value of art. Therefore, when I took the first issue of the magazine in hand, I wanted to take responsibility in the coordination of the second issue of the magazine, since I thought that Şehitoğlu’s personal effort provides an opportunity for a medium even the very existence of which should be considered as positive, although I thought that the publication in question had many flaws due to its novelty.

Because there are so few media which provide an opportunity to artists to present their works in the way they imagine while they materialize the intangible value of art, we do not even notice to what extent the media we have consist of stereotypical models.

REPEATING CYCLES, ANOMALIES AND PROTOTYPES OF IMAGINATION IN THOMAS S. KUHN’S UNDERSTANDING OF SCIENCE

If we can learn to substitute evolution-from-what-we-do-know

for evolution-toward-what-we-wish-to-know,

a number of vexing problems may vanish in the process.1

After a short introduction, we can talk about within what kind of a framework we have invited the artists to work in order to produce the works to be included in the second issue of the magazine. For the second issue of the magazine to be published in December 2020, we have invited artists to produce one work each to be presented in a periodical by taking into consideration the framework that we have created under the title “Repeating Cycles, Anomalies and Prototypes of Imagination”. We use these concepts directly in the meaning used by Thomas Kuhn. Let’s explain this:

Repeating Cycles – Anomalies – Prototypes of Imagination

Representable time-space Unrepresented time-space First-of-a-kind representations

Within the conceptual framework created by Kuhn in The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, chronically repeating structures, anomalies which cannot be explained by given scientific theories and the mind’s power of bringing order to designs (imagination) have very important roles in the discovery of scientific theories.

According to Kuhn, science is a dynamic system consisting of two phases, namely, the Context of Discovery (Extraordinary Science) and the Context of Justification (Normal Science). The Context of Discovery is the period of scientific activity in which scientific hypotheses are put forward through subjective factors such as intuition, imagination, admiration and habit related to induction, while the Context of Justification is the period of scientific activity in which these hypotheses are tested through objective criteria such as observation, experiment, measurement and deductive logic and the failed ones are eliminated.1

However, the relationship between these two contexts of scientific activity is a circular relationship, because during normal science, the elimination of all tested hypotheses as failed evolves into scientific crisis and scientific crisis into extraordinary science where different intellectual approaches are developed and theories consisting of new scientific hypotheses are put forward. On the other hand, if these new theories put forward also cannot succeed during the process of extraordinary science, science returns to the theories dominating the previous paradigm and to the process of crisis. However, as it is seen, the Context of Discovery, where different intellectual approaches (intellectual prototypes) are developed and subjective factors such as imagination step in, does not occur indeed due to successes in our activity of knowing, but on the contrary, due to a failure in our activity of knowing and the crisis related to it. The most important factor leading to the crisis is the phenomena which cannot be explained by the prevalent way of thinking which dominates the paradigm. These phenomena are each an anomaly within Kuhn’s conceptual framework.

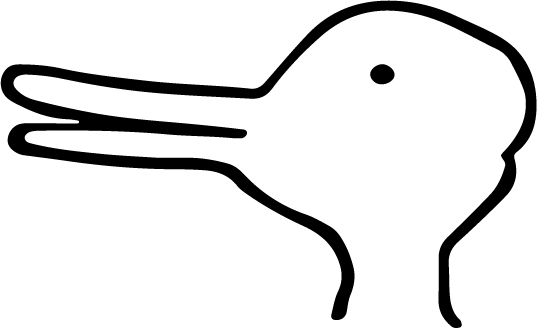

“Ambiguous figures such as the famous duck-rabbit example are used by thinkers, such as Kuhn and Hanson, who defend that, in science, there cannot be any observation independent from the theory, as the prototype of each kind of human perception but especially of scientific observation.” This statement belongs to Nilüfer Kuyaş who has translated “The Structure of Scientific Revolutions” by Thomas S. Kuhn, while the emphasis belongs to me. We can add to Kuyaş’s statement that the seen duck-rabbit figure is the illustration designed for the cover of a children’s book written by Amy Krouse Rosenthal. At the same time, this illustration is used to exemplify that all observations and scientific hypotheses depending on observation are not tested on their own but always as a system of premises, namely, that scientific hypotheses are theory-laden, and therefore, there are difficult cases where we cannot decide which premise the phenomena verify within the theory. This thesis is known as the Quine-Duhem Thesis.

However, although our aim is not to do philosophy of science but to try to understand a philosophy that analyzes how science functions in itself in order to stimulate our imagination as artists, we should be careful about one thing. One of the most misunderstood concepts in Kuhn’s conceptual framework is the concept of anomaly. The classification of a phenomenon as anomaly is nothing else than the incompatibility of a theory (of a representation system) with the various data obtained from the observation of this phenomenon. In other words, regarding anomaly, one should not surrender to the premise that there are schizophrenic objects in nature not acting similarly although they are of the same kind. Anomalies are the source of the data which cannot be explained by the representation-systems created by us with the effort to comprehend the external world surrounding us. And these are only temporarily classified as anomalies in scientific activity: until they are explained by successful scientific hypotheses put forward in the Context of Discovery. However, in science, it happens quite rare for a phenomenon to be classified (acknowledged) as an anomaly, because as Kuhn demonstrates with historical examples, scientists are very committed to the prevalent way of thinking of the paradigm in which they are living. Therefore, instead of doubting the fundamental scientific hypotheses dominating the paradigm, they have doubted the circumstances under which the experiment is carried out or that the counterexamples show up in the application area of the theory.

But then, although, in the phase of normal science, phenomena classified as anomalies try to be eliminated through improvements on the theoretical level on one hand, and through more refined observations on the phenomenal level on the other hand, it is inevitable for a scientific crisis to occur since these are mostly in a periodically repeating structure. (Such as Pluto’s movement around the Sun following an orbit resembling a flower form.) Therefore, eccentric cases classified as anomalies cannot be eliminated despite all improvements on the theoretical level and all refined new conditions on the observational level. Hence, through the accumulation of each of these phenomena as an anomaly, the process of scientific activity causes a doubt in the fundamental scientific hypotheses of the theory (such as the doubt in the accuracy of the axioms of the Euclidean geometry on which Newton’s system of Mechanics is based on), and evolves by necessity into a process called by him as “scientific crisis”. This process leads the scientists to search for a new theory that can explain the anomalies which cannot be explained despite changes in the theory during the process of normal science and pass to the Context of Discovery, and even though for a while, science looks like an irrational pursuit, making scientific hypotheses based on unobjective factors such as imagination and intuition.3

This short summary yet in the form of a draft is certainly not sufficient to understand Kuhn’s Understanding of Science. However, it is quite sufficient to point out to the important role that periodically repeating circular structures, anomalies as the source of the data not represented by our representation-systems, and imagination that makes us create complex language-systems on a level to represent these anomalies have on the human activity of knowing. Moreover, one should not forget that just like the scientists try to explain very different kinds of object domains not by one single scientific hypothesis but always by creating a system of hypotheses (theory) and with the same system that they have established; the artists also project their approach to art to very different kinds of object domains (reflection, daily objects, internal functioning of art, etc.) not by means of one single representation but by creating a representation-system. Therefore, it is quite exciting to see how artists will materialize their approach to art in a medium such as a periodical through their works in the medium in your hand. In this context, we invite the artists to create the prototypes of their imagination about an object that they focus on as an anomaly, by taking into consideration that they will present it in a periodical.

Yağız Özgen

August 2020

1 T. Grünberg, Felsefe ve Felsefî Mantık Yazıları: Thomas S. Kuhn ve Bilimsel Akılcılık [Writings on Philosophy and Philosophical Logic: Thomas S. Kuhn and Scientific Rationalism], p. 287.

3 T. Grünberg, Felsefe ve Felsefî Mantık Yazıları: Bilimsel Akılcılık Anlayışının Evrimi [Writings on Philosophy and Philosophical Logic: The Evolution of the Understanding of Scientific Rationalism], p. 287.